It was around 9:30 a.m. on Nov. 4, 1979, almost 40 years ago, when Mark Lijek, a 29-year-old American Citizens Services officer for the U.S. Consulate in Tehran, heard commotion outside his office.

That day, Iranian students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and captured 66 Americans. The takeover was, in part, a response to the United States accepting Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi into the country for medical treatment. Though 14 hostages were released in the coming weeks, the siege kickstarted the 444-day Iran hostage crisis. Lijek, however, was one of six diplomats who escaped the complex that day and avoided capture.

“The shah had been admitted to the U.S.,” said Lijek, now 68, in an exclusive interview with Homeland411. “Then, in about October, we all kind of expected there would be some blowback from that, but there hadn’t been, so people started to think that maybe it would be all right. But there had been a big demonstration that weekend prior to the takeover.”

The night before the takeover, the consul general closed services for the day in response to Iranians not providing adequate security to the compound. Lijek believes the lack of crowd coming in for services that day may be the reason some individuals in the consular section of the compound were able to get away.

Lijek said the students, as they broke through the courtyard and front door, did not notice them for almost half an hour. However, once the consular workers were seen, demonstrators attempted to reach them by breaking through the second-floor bathroom.

“Our building was very secure,” Lijek said. “I mean, it had bulletproofed everything except for those bathroom windows. We heard the glass breaking, [the guard stationed there] ran in there; I guess he saw somebody climbing up the ladder; he pushed the ladder away and threw some tear gas down into that little square through the window.”

After being on lockdown for an hour, Lijek said the power went off, and the lack of windows made the whole room “very gloomy,” and tension began to rise.

Seeking Refuge

After hours of waiting in the dark, the consul general said the group should seek refuge at the British embassy, per a standing agreement between both compounds. The local Iranian staff was sent home for their safety, but one lady volunteered to remain as a guide for the Americans to reach the British compound. Lijek said the remaining Americans were split into two groups and headed out.

“We did exactly what we were supposed to do; we went out the door, we turned an immediate left along the wall, and we just kept going to the west. The British embassy was west and a little bit south, but we didn’t want to cross the main street where the demonstration was because we didn’t want anybody to see us,” said Lijek, who recalled then that another demonstration was taking place in front of the British embassy, barring them from entering once they arrived at the compound.

“[Our guide] pulled us into an alley and said we ought to reconsider,” he said, adding that she suggested they go with her to her home. “We didn’t think that was a good idea, just because we figured that this might get a little messy and … we just didn’t want to take advantage of her that way.”

According to Lijek, the second group, led by the consular general, was captured after deviating from their course and running into a group of armed Iranians. Robert Anders, one of the diplomats in the second group, tried to go to his home instead of going to the British embassy and avoided capture; he returned to warn Lijek’s group of the incident before taking them to his apartment.

The escaped group stayed in Anders’ apartment for several weeks before they were able to connect with Canadian officials. They then made it to the Canadian embassy, where they stayed for almost three months before the CIA began formulating a plan to extricate them.

Amid all this, Lijek’s wife was part of the six who escaped the compound as well, which worried him perhaps more than anything. Lijek had been there for six weeks before she arrived, and he already realized something was terribly wrong.

“I realized that the guy in Washington—the country director for Iran—had his head in a dark place and had no clue what was going on in the country; he was living in La-La Land, and he was the one trying to bring my wife up there,” Lijek said. “I really didn’t want her to go but … I just felt like I couldn’t derail that plan because it wasn’t personal anymore. Her coming was part of the reopening of the consular section.”

Pressing International Issues

Meanwhile, the United States was also dealing with other international issues, such as brokering the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty following the Camp David Accords and responding to the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. Gary Sick, the principal White House aide for Iran during the years of the Iranian Revolution and the hostage crisis, said at a Council on Foreign Relations panel in February how tough it was to get people’s attention on the issue simultaneously.

“Although … Iran was my beat, I ended up spending an awful lot of time working on the Camp David Accords because that was what was really hot,” Sick said. “But that’s not to say that people didn’t know or didn’t care. There were regular memos describing how things were going wrong.”

Sick explained that the intelligence failure that led to the United States not foreshadowing the revolution came from misreading the shah and believing he would step in to stop the coup.

“Basically, here was a man who had been on the throne for thirty-seven years. He had a vast amount of experience. He had immense amounts of money. He had a huge army. He had a fearsome secret service. He had everything that he needed to deal with this problem. And he didn’t,” Sick said.

The shah originally came to power in 1941 but fled in exile in 1953 for a few days before being placed back on the throne that same year through a joint C.I.A and British Intelligence coup to replace Muhammad Mossadegh, Iran’s newly elected prime minister. Mossadegh had run on a campaign to nationalize the country’s oil industry, which was under American and British corporation control since its discovery.

The new government under the shah was secular, anti-communist, and pro-Western—however, the shah was accused of being a brutal, arbitrary dictator, and many Iranians resented the American involvement in their domestic affairs.

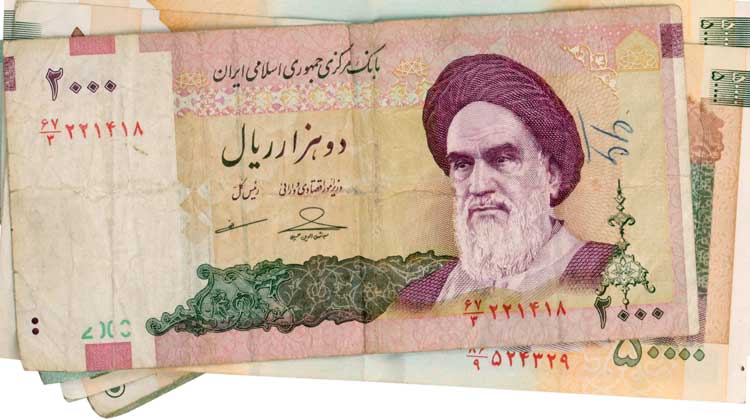

Iranians turned to the radical cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in the 1970s who promised greater autonomy for the Iranian people. Khomeini had been exiled for 15 years prior to his return, and by 1979, revolutionaries forced the shah into exile in Egypt, installing a militant Islamist government instead.

Canadian Protection

Back in the Canadian embassy, it was clear to Lijek the hostage crisis would not soon be resolved.

“The Canadians were wonderful hosts, but they were worried about it,” Lijek said. “We never had any close scrapes, but in January [1980], things started to change; somebody made a phone call from the ambassador’s residence and asked to speak with Joe Stafford,”—a diplomat from the group of six that escaped.

Lijek said those three months in hiding in the Canadian embassy “wasn’t the best of times,” but that he and the others realized “how much better off [they] were than the people in the compound” after hearing updates on how the Iranian demonstrators were treating the hostages. Another factor Lijek recalled was how the confidence-inspiring attitude of Canadian diplomat John Sheardown kept them going during the incident.

Making their Move

By January 1980, a little more than three months after the embassy takeover, a plan came together through a secret joint operation between the CIA and the Canadian government to get the six Americans out of the country.

“When Tony Mendez [the CIA agent assigned to the mission] showed up, that was the 26th of January … and his buddy whose name we still do not know after all these years, just his cover name ‘Julio’ – I guess he was the language guy, he spoke Farsi,” recalls Lijek, about the fast-paced and secretive rescue mission. “Tony briefs us, we vote, and we want to do the ‘Hollywood Option’.”

The CIA “Hollywood Option” involved the creation of a dummy film company scouting suitable filming locations in Tehran and assigning movie production roles to each of the six Americans, who became known as the “Canadian Six.”

“The next day, we get ready, learn our covers and all that stuff, then we have a big party the night before, use up all the booze in the house and then at 4 a.m. the following morning, we’re heading to the airport,” Lijek said. “It was very compressed, and there was no time to reflect on what we were doing or what the consequences might be,” Lijek said.

Lijek and the other five, carrying Canadian passports, boarded a plane in Tehran and flew to Zurich, Switzerland, on Jan. 28, 1980.

“The plan was to not tell the world about us because [the U.S. government] was worried that the Iranians would take it out on the hostages, the fact that we had escaped, that the CIA had been involved, which was never made public, not until ‘97.”

Rescue Mission

Still, after Lijek and the other five’s escape, 52 hostages remained in Tehran.

An initial rescue attempt ordered by President Jimmy Carter in April 1980 proved unsuccessful. Known as Operation Eagle Claw, the risky military mission was aborted when only six of eight helicopters arrived at the staging area in Iran, and then only five helicopters were fit to continue. Then, as the aircraft departed the staging area, a helicopter struck a transport plane killing eight servicemen.

Iran held the remaining 52 hostages until Jan. 20, 1981, just hours after Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the 40th president.

Moving On

In light of the public backfire against the Carter administration over their handling of the hostage crisis, Lijek remembers having to put his own feelings about the government’s management of the incident aside to ensure the remaining hostages had a chance to come home.

“We all felt that the president, the State Department, the entire Washington establishment … took no concern for our safety—they did a lot of really stupid stuff and … people were angry,” he said. “They kind of wanted to know if we were going to be critical of the administration … and it was very tempting, but we just wanted to do what would help our comrades get home, and publicly accusing Carter of incompetence, as satisfying as it might be, would not have furthered that process, so we agreed to not say anything.”

Since the hostage crisis 40 years ago, the United States has not had an embassy in Tehran and now operates from the Swiss Embassy’s Foreign Interest section.

Sandra Sadek is a staff writer for Homeland411.

© 2019 Homeland411